I recently read Sally Rooney’s interview in The New York Times, which was great and to my surprise, was more about her as a public figure rather than her latest novel, Intermezzo (which I still have yet to get my hands on, but rest assured I will grab it when I get the chance!). I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and about her relationship with her work especially. It made me think a lot about how we, as an audience, view authenticity when talking about artists and their creations, and how it’s a lot more nuanced than we may think at first.

My thoughts on Intermezzo will come later, and a quick shoutout to the book that I’m currently reading: Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors and the two books that I recently checked out from the library and are next on my TBR list: Past Present Future by Rachel Lynn Solomon and I Hope This Finds You Well by Natalie Sue.

This is inspired by a recent essay I read on the “authenticity industrial complex”, a term coined by the author, which made me think about boundaries, both on the Internet and in real life, and if it’s possible to have them while also being your true self.

I hope your Fall is off to a great start and I hope this essay is finding you when/where you need it. Enjoy!

The word “authenticity” used to mean something. There was a novelty about it, before it was coined into a buzzword that would permeate our social media feeds and cultural discourse. Authenticity is loosely defined because it means something different to everyone, yet we’ve managed to narrow it down to baring yourself on the Internet, sharing emotional personal stories and being “vulnerable”, which even now is considered a performance if you’re not careful. We’ve boiled down something as vast and complex as the human condition into a checklist of sorts, asking ourselves if a creator in a video means an apology, or if a story being shared has the correct amount of depth and substance necessary for it to be deemed real. For music to resonate, it must be diaristic and specific - good isn’t good enough anymore, you need to stand out by giving everything away, at all times.

Is this good for us? Are we all really benefiting from sharing chunks of our life so thoroughly and transparently? I’d argue that in some cases, it has the really wonderful quality of connecting strangers to one another. But the way authenticity can be received by an audience changes everything. You can do everything “right”, and it still might not be enough. And this doesn’t just apply to social media, but real life interactions as well, where we’re all constantly engaged in self-monitoring as we interact with others, asking ourselves if our performance was believable enough, if we were likable for others while also remaining truthful to our values.

This is a narrow line to walk, because it’s impossible to not perform, to a certain extent. We show different parts of ourselves around different people, and that’s natural. The way we act around our coworkers isn’t how we are around our friends and family. These distinctions are there because it helps us make sense of our relationships and how varied they are, as opposed to just grouping them all together, which makes things messy. Authenticity is also linked heavily with trust. We’re more transparent with people that we’re comfortable with as opposed to strangers. This is what makes the authenticity phenomenon on the Internet so interesting - we see really intimate content coming from strangers on our screens, which creates this false sense of knowing, and makes space for intense, consuming parasocial relationships.

Author Sally Rooney, who has been considered the voice of a generation, is an interesting example of this because she separates her public life from her works of fiction, yet many see her as this literary icon and the leader of the literary sad girl movement, which is something that she has suggested that she doesn’t relate to.

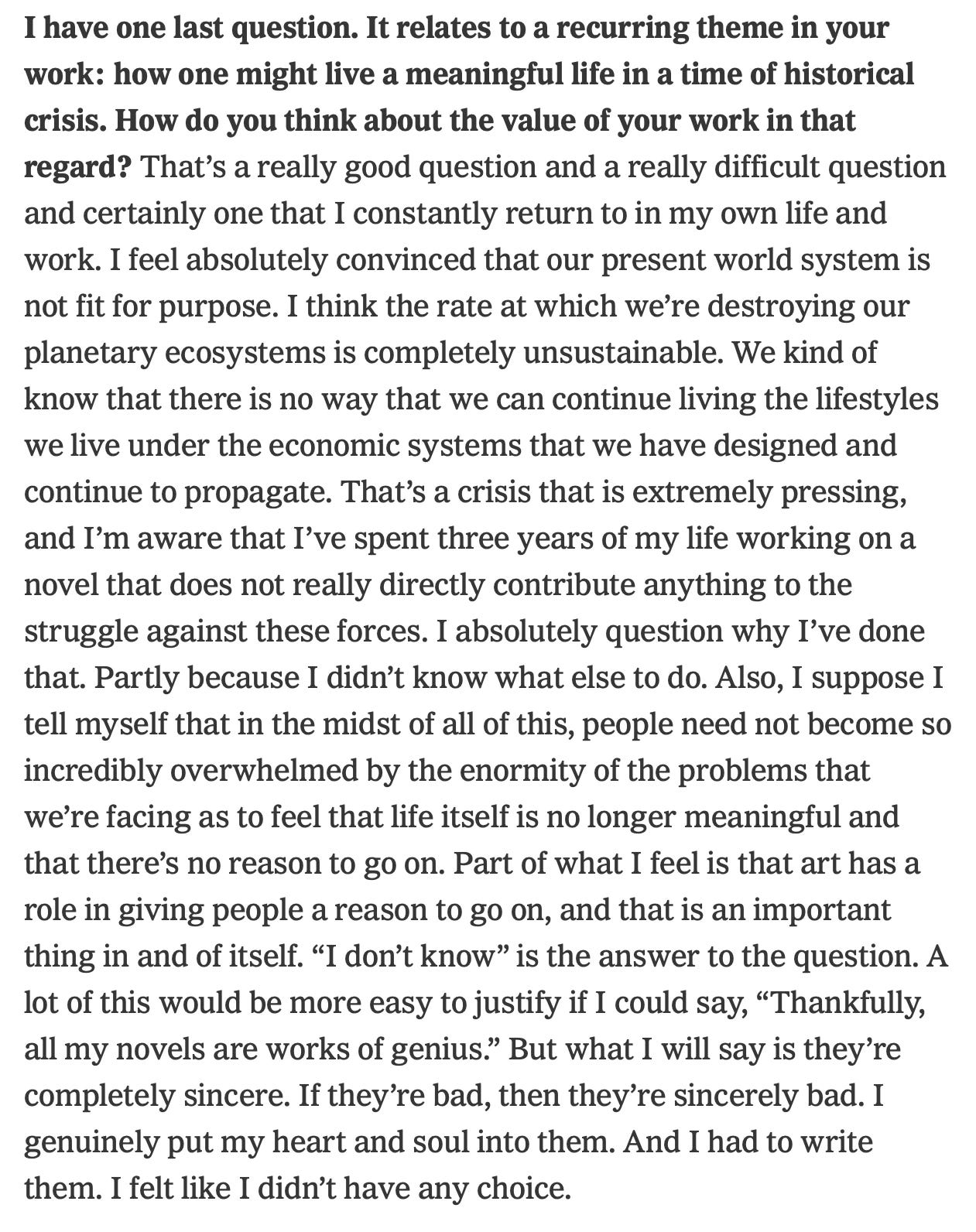

Excerpt from Sally Rooney’s interview with The NYT

What Rooney discusses in this excerpt is a detachment from her work as a person, and having her novels stand alone as bodies of writing rather than extensions of her life. This contrasts greatly with someone like Taylor Swift for example, who’s also considered the voice of a generation but writes her music from a detailed first person point of view that acts as a lens into the most intimate and personal moments of one’s life. Neither are right or wrong, it’s all a matter of perspective. This is why I take issue with our culture’s repackaged take on authenticity, and how there is an element of “How believable is this?” rather than accepting people for who and what they are. How much you decide to share should be your choice, and you shouldn’t have to deal with pressure from others when it comes to being vulnerable. How strange would it be if we asked incredibly personal questions to strangers in real life? If we spoke like the comment section of a Tik Tok post, asking someone about a health condition or a messy breakup, how would that go down in an actual conversation? It’s worth noting how much we try to replicate social media as real life when it’s just not the same, no matter how hard we try to make it.

Here are some more excerpts I really liked from the interview!

All of this is to say that I think authenticity is complicated and different for everyone. Some of us may benefit from sharing our stories and connecting with others, while others may feel comfortable connecting using different aspects of their lives and choosing to keep what they want private. For example, Rooney’s method of connection is through her work, while she maintains a public life and speaks up when she feels is necessary, and those two parts of her life remain related to one another heavily, but also separate in their own right. And as we continue to see a rise in surveillance on social media and monitoring others as well as ourselves, we should all be asking ourselves, without the influence of others, “What do I actually want to share with the world?”

There’s so much academic (among other kinds of works) literature on this topic and how we perform our identities especially. And it’s definitely something I grapple with a lot. I think we do perform a lot and the way in which we post our lives on the internet influences that performance. I think this can be examined in the emergence of a new *insert* “core” every other week, always grasping at a collection of feelings and ways of being wrapped up into an aesthetic that dictates fashion, interior design, car choice, hobbies, and other consumerist decisions. There’s a part of me that feels like this is just part of our existence and is a way of negotiating belonging within a group, but there is a sinister capitalist, individualistic nature to this kind and amount of performance. People are also desperately searching for something real, so the more “raw” and immersive content (hopecore, posting extremely intimate content of families and relationships are examples of this content) is, the more we can perform what it feels like to be submerged into the depths of human condition, yet we run from it at the sight of true horror (war, natural disaster, etc.).